who’s gonna mentor the next generation if we’re all walking around with main character energy?

the sky has been falling for at least as long as i’ve been alive

yet every morning, the sun tises again

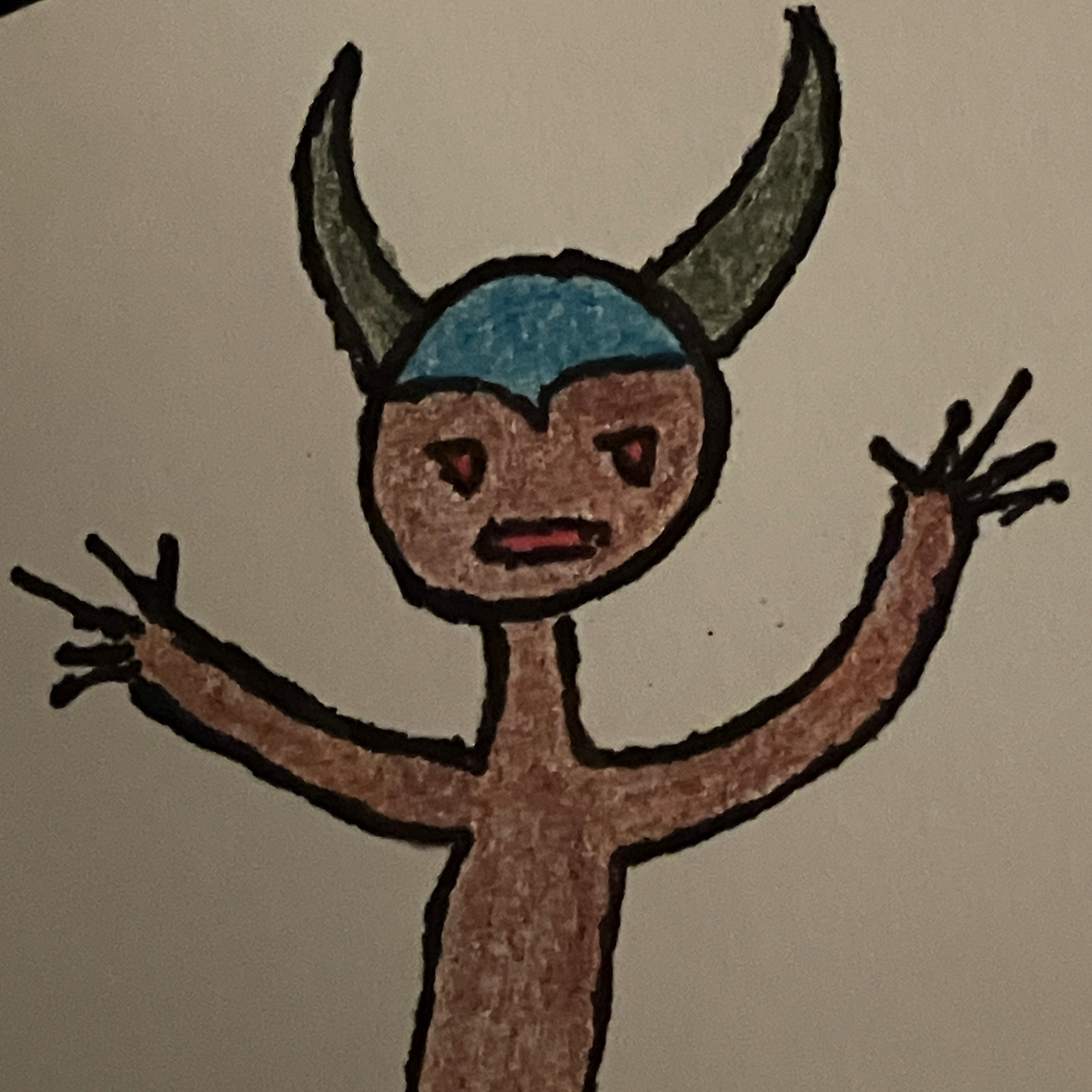

y’all, my writer brain is ON-

one of last night’s silly sketches evolved into an idea for a children’s book, a genre i’ve shown no interest in

time to figure this thing out if for nothing more than the sake of neuroplasticity!

an unexpected bit of writerly news: i might have an idea for a children’s book

who the hell have i become?

it’s been said that the only thing that can grow forever is cancer

but even cancer must stop once it’s killed its host

Y’all,

If a lifetime of writing has taught me one thing: It’s not enough to simply write good. Ya gotta market and sell your craft too.

So, what better place to start than here, with a small number of people who know me better than online strangers?

I recently finished the first pass of my novel, working title A Perception of Time. It’s a grief novel that focuses on the passing of time (whatever that means at various monents).

There’s still so much work to be done, because it’s a mess in three parts:

- The manuscript itself.

- Scenes I haven’t fit into the novel yet.

- So many notes for revisions.

I can’t wait to share it, but the time ain’t here yet. I imagine I’ll spend 2026 on a second pass to prepare it for some beta readers.

But I’ll share the current version of the dedication so you know what’s coming down the pike:

To my father—

Sorry we let time get in the way.

And to my son—

May we do better.

…

And then the epigraph:

‘I was born into an abundance Of inherited sadness’

(From ‘Jacksonville Skyline’ by Whiskeytown)

…

It’s a deep fried absurdist tale with an unreliable narrator (because let’s face it, we’re all unreliable narrators. Our memories of events are as faulty as the people involved in said events).

I like to think it’s sophisticated without being pretentious, which is my official goal with everything I write.

The novel also ties into a collection of stories I’ve been working on for the last five years or so. But I realized I was working on a collection only a year or two ago. Life works out that way every once in a while. As a wise man once said: You think it ain’t be like that, but sometimes it do.

Who knows what will actually happen with the novel, but right now I’m leaning toward self publishing it as a free ebook in EPUB format. Hardly anyone makes real money from the books themselves—but books are great marketing. What better way to get myself out there? Maybe it could lead to a side gig in being a writing coach. (Forgive me for tooting my own horn, but you can’t rely on others to do it for you: I’m a damn good writer for the right kinda reader.)

Unless I soon die unexpectedly, the novel will see the light of day at some point. But how much time will pass—or what will be our perception of it?

I can’t comment on that.

to the oil and gas professionals still angry about portrayals in the show landman:

i get it. i see you. i hear you.

as a writer, i hate how the shining has stigmatized writers.

we don’t all go crazy at some remote hotel and axe through doors and terrorize our families.

most of us do that at home.

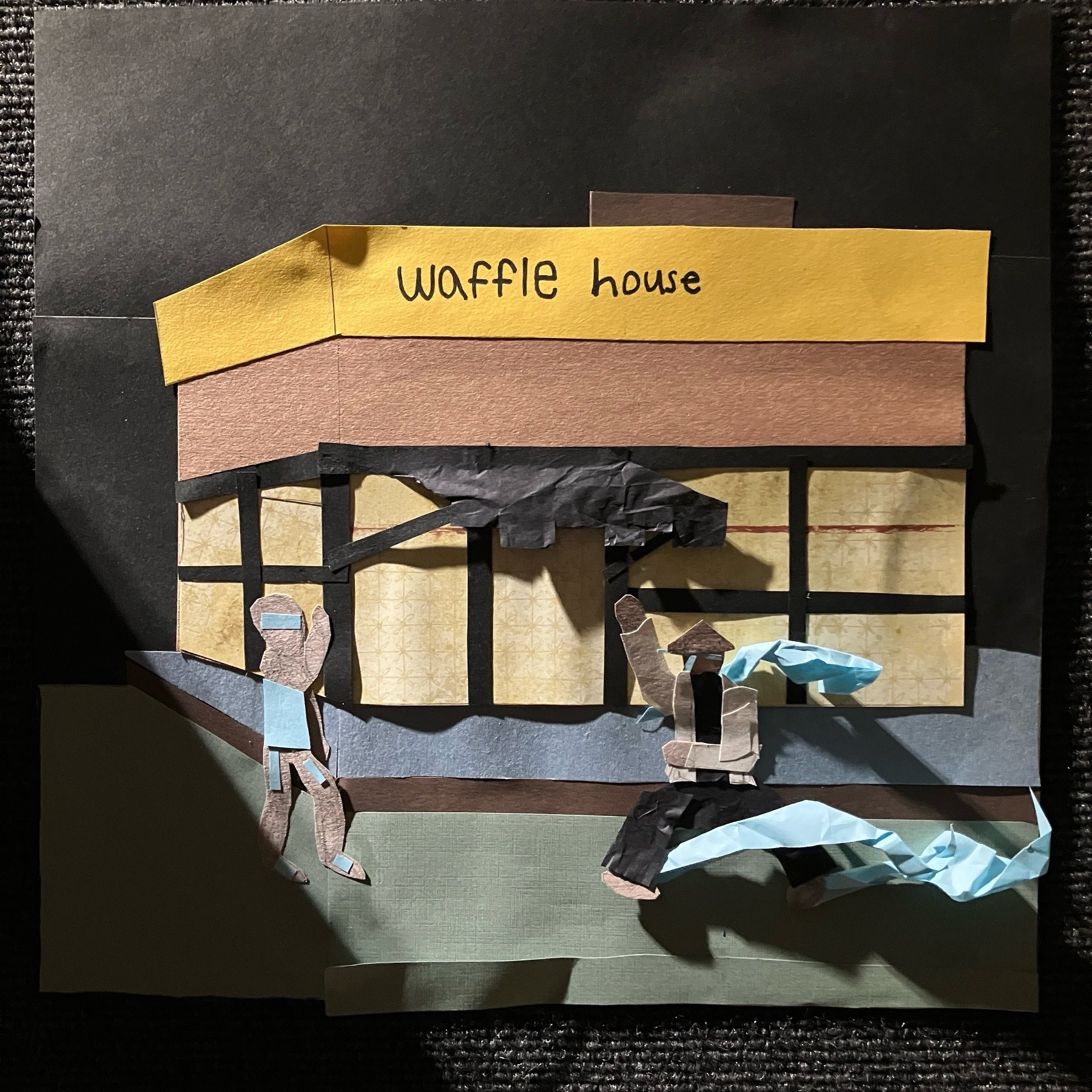

thing number five thousand thirty-seven no one tells you about parenthood:

you better have a second home to keep all your kids' artwork, because HOW DARE YOU EVER throw any of it away

and don’t even think you can argue you gotta get rid of something to make room for the new

they ain’t falling for that one

just got a strange look and a laugh from the guy at the mcdonald’s drive-thru

yeah i’m dressed as a unicorn, but i still deserve dignity and respect, dammit

‘Another way to see it is that AI is a mirror, not a monster. It reflects who we already are, not some alien intelligence invading from the outside. The truth is that those who care deeply about art, music, or education have always been a minority—and often dismissed as “elites” by a public that prefers reality TV, sports betting, or cat videos to the human search for meaning. Our technologies simply reflect our collective nervous system.

AI doesn’t create new impulses; it automates the ones we already worship. We prize stimulation over stillness, belonging over authenticity, efficiency over depth. The “soullessness” we fear in AI is really just the hollow echo of our own cultural emptiness.’

the idea that ai will take your job is scary, not because it’s truly capable, but because those in charge insist it’s more capable than it truly is

you lose your job

quality goes down

customers suffer

only one party wins in this scenario

yesterday:

on the way home i saw a kia soul

nearly rearend another kia soul

and now i can’t stop thinking

about the impact we all feel

when souls collide

The downside of self improvement

For much of my adult life, I’ve been focused on self improvement, a noble cause as I’ve had plenty to work on: awkwardness in social settings, emotional intelligence, communication of needs, and so on.

Self improvement implies you’re working on yourself, which sounds like a worthwhile endeavor. But I now realize that there comes a certain point in which self improvement is no longer the grandiose master strategy it once was. Because, if you’re always focusing on self improvement, then you’re always focusing on what’s wrong with you, while overlooking on the positive aspects that make you who you are.

At some point, if you put in the proper work, self improvement must lead to self acceptance.

We’re all imperfect. We’re all works in progress. And we'll never reach many of the ideals we strive for. We’ll never reach that state of perfectly consistent enlightenment.

Life is a journey, and the roadmap that worked yesterday may not work tomorrow.

If you’re on your own self improvement journey, please be sure not to focus on the goal of perfection or idealism. Instead, make sure to work toward the goal of self acceptance. Make sure you’re improving yourself to a point in which you have no problem being in the same room as yourself. (What other alternative is there?)

At some point, when you see certain faults and shortcomings within yourself, you must accept that you’ve reached the Pareto Principle of self improvement: You’ve fixed 80% of what’s wrong with you, and you’ll tweak the remaining 20% later, because you know you’ve reached the point of diminishing returns. And now, you’re at a point where the better strategy is to focus on improving or highlighting your strengths, because therein lies the greater return for your time and efforts.

The last step of any self improvement journey should include accepting and--maybe, just maybe--also loving yourself. Otherwise, what was it all for?

Welcome to the Multiverse

Are we living in a Multiverse? And, if so, how would we know?

Those are some of the questions I asked myself on a recent morning commute. (You can blame my work-in-progress novel for such thoughts.)

Shortly after asking these questions, I realized we definitely are living in a Multiverse—just not in the way most of us imagine.

For much of the 21st Century, each of us has been living in our own reality. Because there's now no shared reality, no shared truth. No shared narrative.

In the 21st Century, truth is irrelevant for many of us. Unless it supports our biases and viewpoints. The validity of a claim is less important than its source, which determines whether we accept or reject the claim.

As monoculture has withered away around us, we've thrown away collective ideals and have instead chosen to focus on the small differences that separate us. We find a group or two to attach ourselves to, and we build our worldview around the groups' ideals. Instead of finding groups that match our evolving beliefs, we halt our own growth by staying true to the group rather than staying true to ourselves.

In a world full of constantly changing variables, we treat our views like constants, static and unmoving. We stay trapped within our own realities, never considering how we might merge certain parts of our realities to create something more functional for more people.

Our realities stay fragemented, just like in a Multiverse.

When the Simulation reveals itself to you, believe what you see.

Where the hell have I been?

Sorry I went silent on y'all for a while.

My intent has been to release at least one newsletter every couple weeks. But I've obviously slipped.

But for good reason:

As the seasons of the hemispheres are changing, so too is the season of my existential crisis. (I once thought my life was a series of existential crises, but I've recently realized it's just one extended crisis. It's like when that street you're on changes names. Sure, you can call them two different streets, but they both follow the same paths and lead to the same places.)

Any good existential crisis leads to the question: What's the point?

And that's the question I've been asking about this newsletter. I don't mean it in the tone of 'What's the point? Should I keep going?' I have no plans to stop. Instead, I'm asking what the hell is worth writing and sharing. Sure, to some degree I write for myself. But let's be honest: I put my writings online in the hope they'll be read.

My writings tend to be all over the place, so I feel as if different readers enjoy and expect different things.

Is my voice enough to carry this newsletter? Or do I need a particular focus?

Drop me a line if you have any insights to share!